When two tribes go to war a point is all that you can score

Readers of a certain age will recognise these words from Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s 1984 mega-hit, Two Tribes. I was reminded of it the other week after seeing Andrew Haigh’s remarkable film, All of Us Strangers, which features their follow up hit, The Power Of Love, and attending a talk given by Tony Blair’s former aide Alastair Campbell, on consecutive nights.

First the film: I’ve been fortunate to see Andrew Scott on stage and screen many times: he is so watchable, and brilliantly inhabits every character he plays. His Hamlet at The Almeida was stunning. His performance in the Old Vic’s revival of Noel Coward’s Present Laughter was hilarious, and exhausting just to watch. His achievement in All of Us Strangers is equally remarkable: to do so much with so little (the dialogue is sparse to say the least) shows an exceptional actor at the top of his game.

While the focus of the film is a relationship between two men, and the relationship between one of them and his dead parents, it’s also about love, romantic love of course, and the love of parents for their children, but also (not that this is anyway explicit in the movie) the capacity we all have, or can have, for love our fellow human beings. As the credits rolled and Holly Johnson sang his heart out, I couldn’t help but feel how little of that kind of love is apparent in today’s world.

The following evening Alastair Campbell was interviewed by Josh Glancy of The Sunday Times at Union Chapel. Campbell is not everyone’s cup of tea, but his insights into British politics, and especially the hurdles facing Labour getting into power and making the most of it (if and) when they do, are second to none. He was less impressive, however, when questioned on the situation in the United States, and in particular why the polls are putting Donald Trump ahead in the race for the White House:

I find it unfathomable …. I just don’t know what’s happened in the American psyche? I just don’t know the answer to that question.

To be fair to Campbell, it’s not straightforward. But this is a crucial aspect of the current political reality. There’s already evidence of this deadly infection of the body politic spreading across the Atlantic. Britain’s two previous Prime Ministers have both recently given the strong impression of endorsing Trump. Last week Liz Truss appeared alongside Nigel Farage at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in Maryland. The Guardian chose to lead on the fact that Truss was ‘greeted by gentle applause and dozens of empty seats’ but we mock such people at our peril. In just 50 days as Prime Minister, she succeeded in making millions of mortgage and pension-holders considerably poorer for years to come. Farage was the architect of Britain leaving the EU, in the process doing inestimable damage to its long-term economic prospects. And there is every possibility that Donald Trump will be back in The White House this time next year.

It’s not enough to say ‘okay, neither Truss, Trump or Farage, nor indeed Boris Johnson are serious politicians’. Yes, they all lack personal integrity, are deluded about their own abilities, and exhibit a lack of empathy usually found only in psychopaths. But that’s not the point. The world has changed to such an extent that deeply unpleasant, narcissistic individuals such as these can now manoeuvre their way into positions from which they are elected to power (ring any bells?) This would not have happened even twenty years ago. Working out why it’s happening now should be top of every political analyst’s to do list. On Monday night Campbell talked at length about how the world has changed since he was helping Tony Blair win elections, but in this essential regard, he had little to say beyond ‘I just don’t know’.

This is not good enough if we’re going to succeed in protecting democracy from these unhinged megalomaniacs and others like them. Democracy may not be perfect, but in many countries it has long provided a bulwark against despotic rule by a self-interested cabal. Once democracy goes, civilization takes a massive step backwards.

Twenty-seven years ago, when Campbell and Blair had their eyes on Downing Street, I couldn’t have imagined writing these words. And while hideous wars rage in Ukraine, Gaza and Yemen (not to mention Sudan, Myanmar, the Mahgreb and all the other zones of conflict that get little media attention), of equal concern are the culture wars that so distort political discourse. This is a discourse dominated by two tribes, only vaguely adhering to the old values of left and right, and neither of which has any coherent vision for the future beyond ridiculing and insulting anyone who doesn’t share their views.

But the culture wars are a symptom, not the cause, of our current problems. The root causes lie much deeper, and that glorious summer of 1984, when the sound of Frankie Goes to Hollywood was impossible to escape, and Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan were ripping up the play book of economic orthodoxy, is a good place to start.

Actually, it goes back even further, to the years after 1945, when people started to realise that their lives need not be a constant struggle, and that politicians and the institutions of state can play a significant role in shaping society. As civilization develops, it can, as I have outlined elsewhere, go in one of two directions: towards greater inclusion, with the result that more people have a better experience of life than their parents’ generation. Or towards greater exclusion: where the interests of a small minority of citizens are favoured over those of the majority.

Post-1945, western governments wanted to create conditions in which the experience of the preceding three decades (two world wars, the great depression and the Holocaust) could not be repeated: they enacted measures to ensure economic stability and sustained growth, leading to greater inclusion. Then, in the 1970s for reasons too numerous and complex to go into here (a piece on this will follow), the economic foundations on which this success was built were removed. Society stopped becoming more inclusive, and the post-war aspiration of people for lives better than their parents’ started to unravel.

I doubt that the architects of this Thatcher-Reagan economic revolution realised what the long-term outcome of their reforms would be. But whatever their intentions, and even if they were sincere in their belief that free market reforms would boost growth and improve things for everyone, it didn’t work: many people’s experience of life no longer matched their aspirations and, crucially, they didn’t understand why, beyond a hunch that it was all the fault of politicians, and what they would later be encouraged to regard as the interests of a ill-defined elite.

Many analysts refuse to acknowledge that the crisis in politics today has anything to do with the economic changes of the last four decades. It’s true that not everyone who voted for Donald Trump in 2016 is poorer than their parents. But too many people heap blame on things that are symptoms of our failure to build on post-war economic progress, rather than making the effort to understand the underlying context.

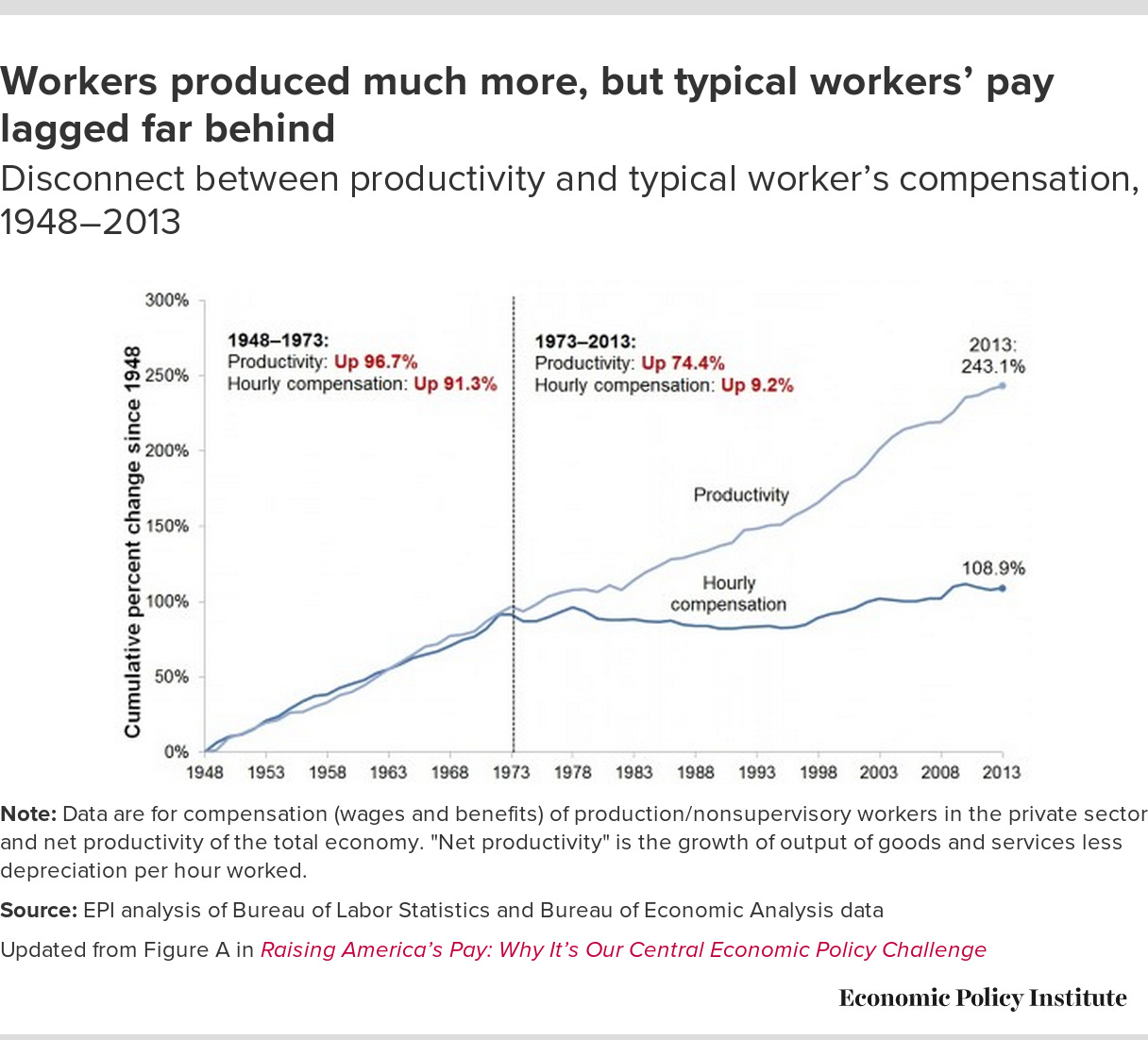

The internet is awash with graphs showing how real wages (especially in the United States) have stagnated since the 1960s, but these two charts, taken from this excellent report by the Economic Policy Institute in Washington DC, give some idea of how badly the economy has failed to deliver for ordinary people in recent decades:

Productivity has improved continuously in the US since 1948, and for 25 years wages kept up. But since 1973 real wages have remained pretty much where they were for five decades now. You could argue that the period 1948 to 1973 was a blip. Post-war economic conditions were untypical, and after 1973 things simply returned to how they had been previously. That’s true, but it’s not difficult to see the impact on the perceptions of people whose wages have stayed the same while the cost of living has rocketed.

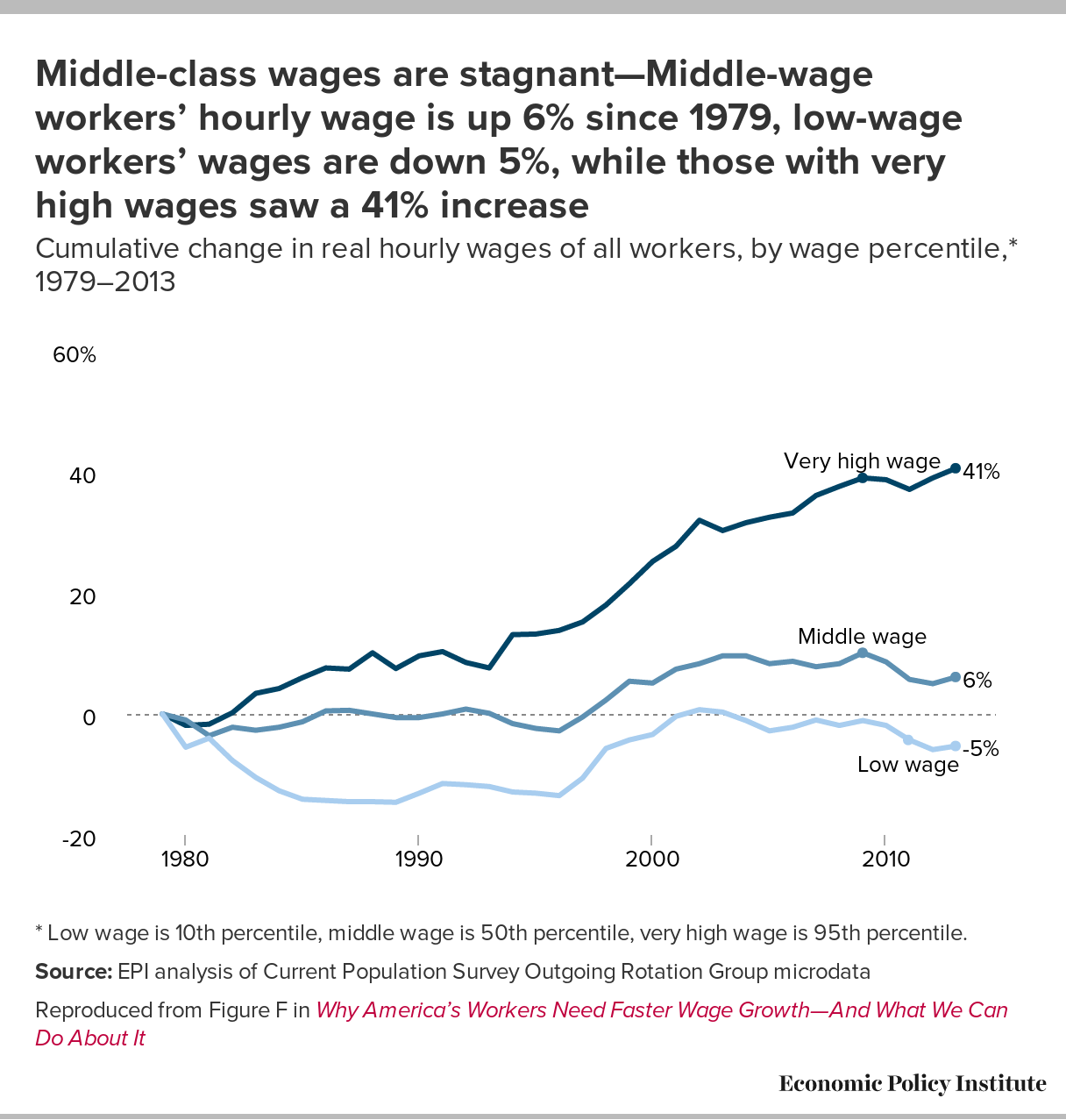

So there is an understandable perception among lower earners that things are getting worse. But, as the next graph shows, this isn’t the experience for everyone. And this fact can only compound the sense of exclusion and injustice felt by many people.

The post-war period may indeed have been a blip, but it was a period during which things improved for most people. And it was the decisions of elected politicians in respect of economic management and regulation that made the difference. Post-1973, politicians changed course and handed control of many of the levers of economic policy to the markets, with inevitable results.

I understand those who argue that it’s not just about economics. The beliefs and opinions of many of those who vote for Trump are not the result of any rational analysis of changes in economic policy, but they are a consequence of the social and cultural changes those policies have brought forth. Changes that would not have happened had the real value of everyone’s earnings remained on the path of fairness and inclusion that they followed from 1948 to 1973.

While the free market reforms of the last half century have done nothing to improve economic growth, huge quantities of new wealth have been created. The second graph shows a massive change in how that wealth is distributed. To use the framework of classical economics: the proportion of wealth earned by the owners of land and capital has increased considerably at the expense of labour. I have no doubt that Adam Smith and Karl Marx (great classical economists both) would have been appalled at this state of affairs, and if alive today would be making dire warnings about the likely consequences on their substacks, albeit more eloquently than me.

In a democracy, as much is decided on instinct as it is on knowledge, reasoning, understanding and even truth. If you accept this, it’s a short step to realising why a sizeable chunk of disillusioned Americans have given up on conventional politicians and decided to throw in their lot with Trump. Some of his supporters are clearly as deranged as he is, but 63 million Americans didn’t support him in 2016 because they are mad, nor did an additional 9 million in 2020.

The best thing about democracy is also the worse: anyone can stand for elected office but gross incompetence is no bar. When people feel they have nothing to lose; when they conclude that the political class has abandoned them; when they read about the explosion in the number of billionaires as they struggle to put food on the table, they will vote for anyone who is different, just to see what happens.

Yes, the United States in particular is a culturally complex society, so much so that it sometimes feels like a laboratory experiment. The results coming out of the lab are currently very worrying, but not so hard to understand when you look at the economic reality. One thing is clear though: the great democratic experiment will fail unless the economy is re-constructed along lines that deliver a much less unequal society; and until politicians, the media, schools, universities and all the other institutions that shape society and people’s understanding of the world, acknowledge the paramount role of economic failure, consequent social exclusion, and people’s perceptions of injustice in the current crisis.

Back in 1984, when Holly Johnson won the Ivor Novello award for Two Tribes, it was the cold war and the threat of nuclear annihilation that weighed heavily on our future prospects. With that outcome once again a possibility as democracy comes apart at the seams, we desperately need new leaders; leaders who understand where we went wrong and recognise the need for fundamental change, especially in respect of the economy.